- Thursday, April 24, 2025

While the Hindu nationalist party set up narratives against the only woman chief minister of the country and her party before this year’s general elections, the ground reality was completely different.

By: Shubham Ghosh

WHILE the less-than-satisfactory show by prime minister Narendra Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in the recent general elections in India has left his highly energetic constituencies devastated, the exact opposite has taken place with the followers of Mamata Banerjee, the chief minister of the eastern state of West Bengal and one of the BJP’s major foes in the current Indian politics, and more specifically, in her state.

Banerjee’s Trinamool Congress (TMC), which will complete 15 years in power by the time Bengal goes to polls in two years’ time, was expected to lose a major ground to the BJP in this election, something that the exit polls had also forecast. Some even anticipated that the Hindu nationalist party’s seats would be more than that of the TMC.

Banerjee’s critics were confident that her downfall would start in this election, thanks to various factors such as corruption, job scam and Sandeshkhali. But none of them actually worked on the ground and the party ended up with 29 seats, more than double than what the BJP got – 12.

The TMC even defeated Adhir Chowdhury, the last remaining big name of the Indian National Congress from Bengal, in this election, by fielding a debutant, a former cricketer, against him. The Congress ended up with one seat, half than its tally of 2019 while nothing was left for the Left, which has now drawn a blank in a series of elections in Bengal, whether national or local.

Read: Why Modi’s BJP was left shocked at Ayodhya, its Hindutva powercentre?

In the 2024 general elections, two anti-incumbency moods were prevalent in Bengal. One was against the Modi government in New Delhi and another against Banerjee in Kolkata.

Read: Coalition era returns in Indian politics: Can Modi do a Vajpayee?

But while the BJP failed to capitalise on the anti-incumbency against the TMC, the latter made full use of that against Modi.

One of the reasons for this one-sided result was that the anti-incumbency mood against Banerjee got divided between the BJP, Congress and Left but the anti-Modi incumbency vote completely went into the TMC’s ballot box.

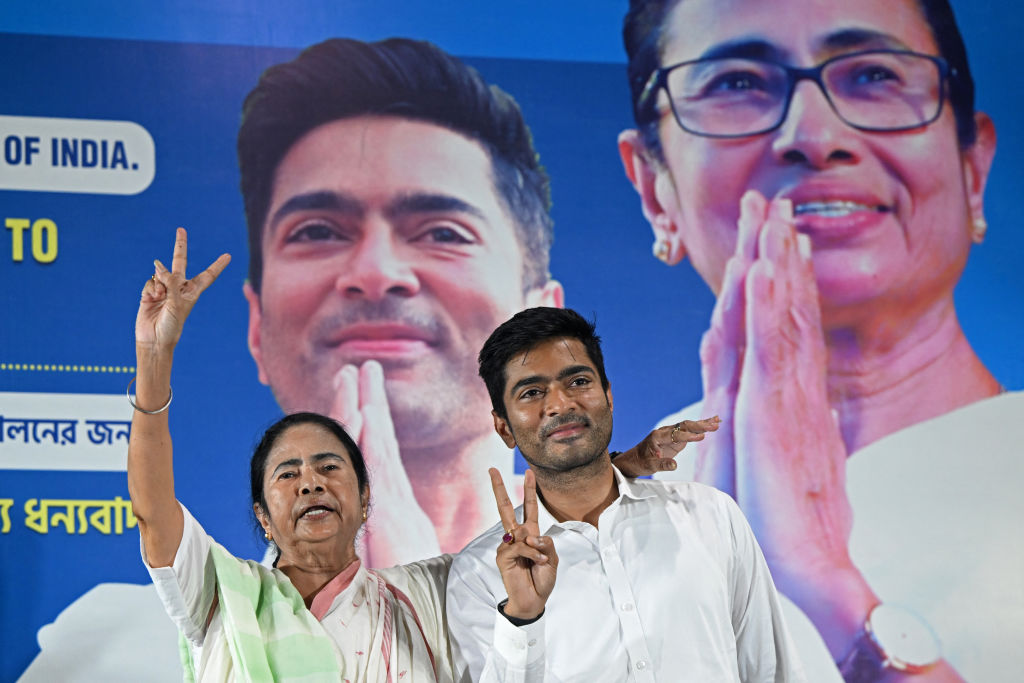

It was not by chance that this happened and there lies the TMC’s credit, especially the Banerjee aunt and nephew — Mamata and Abhishek.

Banerjee is at her best when she dons the mantle of a crusader and agitator. The TMC leader knows very well that while the administrator in her never matches the opposition leader in her, she never went after a national ambition this time and remained anchored in her state where she played the role of an opposition to Modi and his government’s allegedly ‘biased’ politics of denying Bengal its due. Abhishek Banerjee also constructed an effective narrative over this ‘step-motherly’ treatment of the state and even staged a protest in New Delhi last year targeting the Modi government.

The Modi government’s equally stern stance vis-à-vis the Mamata government over releasing central funds eventually helped the state government’s narrative. One report, for example, said that New Delhi withheld funds to the tune of Rs 7,000 crore (£659 million) under the National Food Security Act to Bengal since the prime minister’s photographs were not displayed at all ration shops in the state despite being told. The narrative was a perfect one for the state government to convince people who were at fault here.

The above also helped Banerjee to drive home her point that the BJP is essentially a party of outsiders, something that never suits to the Bengali identity. Like it had happened in 2019 when she had targeted the Hindu nationalist party over the vandalism of a statue of Bengali social reformer Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar in Kolkata, she again targeted Modi’s party with the weapon called Bengali sub-nationalism. It is an irony that the TMC supremo herself had fielded in this election a number of non-Bengalis, like Shatrughan Sinha, Kirti Azad and Yusuf Pathan, but yet successfully convinced the electors of her state, especially the rural electorate, including migrants, that the BJP was not here to do good.

The TMC supremo was also very cautious when it came to openly identifying herself with the opposition Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance (INDIA). Since the Indian National Congress was in a poll arrangement with the Left in the state, Banerjee ensured that she was not sucked into the same by projecting her party as a member of the INDIA bloc. Having fought the Left all through her life, the Bengal chief minister made it categorically clear: she is a part of the alliance but is in no contact with the Congress and Left in the state. Apparently, it looks confusing but for Banerjee, the priority was clear. She would not compromise where she is the strongest player.

Banerjee also bought trust of her constituencies at a time when the Modi government was allegedly denying the state its due by doling out schemes. She started giving educational grants for child education through ‘Kanyashree’ and direct cash transfers through ‘Lakshmi Bhandar’. For the urban voters, this is nothing less than buying votes through bribes but for the fringe people in a state where industries are few and employment opportunities are scarce, these aides mean a lot, particularly for the women.

There is no denying that Banerjee accomplishes a brilliant connection with the women of her state. Slogans such as ‘Bangla Nijer Meyeke Chay’ (Bengal wants its own daughter) during the Bengal election of 2021 were an instant hit. The TMC leader gave women a tool of empowerment through her schemes and made them believe that they could be discontinued if not many representatives of the TMC could reach the parliament. This way, each beneficiary was turned into a loyal vote that the party got.

Banerjee’s government has issued millions of caste certificates across the state since coming to power in 2011 and last month, the chief minister even threatened to defy the high court’s order to scrap the Other Backward Classes status of several classes, saying she could go to the Supreme Court if that happened.

The flawless combination of creating a patronized class (Duare Sarkar or government at doorsteps initiative that Banerjee’s government has started time and again) and fearlessly backing it, something that comes naturally to the firebrand leader, played a massive role in securing a victory in the ballot boxes for Banerjee.

Those criticising her could still ask why scams related to black money or jobs did not make an impact on the TMC’s result? The supporters of the party will invariably point fingers at similar events happening at the national level. For example, for a Sandeshkhali, there is always a Manipur. If Banerjee’s government is accused of stifling freedom of the media in the state, her supporters will ask questions about the central investigating agencies’ alleged over-activism targeting the opposition. These completely neutralised the potential of the opposition to corner Banerjee.

The BJP also failed miserably in mobilising the Hindu voters in Bengal while Banerjee excelled in mobilising the minority votes.

Sabyasachi Basu Ray Chaudhury, a veteran political observer, told The Hindu businessline, “Around one-third of the population in West Bengal are not with the BJP. One out of three persons in the state is from the Muslim community, and they are not with the saffron party.”

It was not a thoughtless move when Banerjee criticised some of Bengal’s old and renowned Hindu organisations such as ISKCON, Bharat Sevashram Sangha and Ramkrishna Mission. She knew that her votebank was getting consolidated.

The BJP conceded that movements such as the inauguration of the Ram temple in Ayodhya were welcomed and celebrated by the people of the state but that did not translate into votes. The delivery on the ground by the junior Banerjee’s corporate-like functioning is also a point why the BJP struggled with its weak organisation in drawing the Hindu votes. Contentious issues such as the Constitution Amendment Act and National Register of Citizens did not help the BJP either, which even lost in one key seat in North Bengal where the minister of state for home affairs Nisith Pramanik lost.

Banerjee’s critics will continue to be disappointed in future elections as well if they judge her politics in terms of good, bad or worse. Given the kind of realpolitik she follows, it is virtually impossible for her opponents to snatch an election from her in Bengal. A Modi wave will do as much as it did in 2019 but that’s about it. To make real inroads in Bengal’s politics, parties such as the BJP, Congress and Left will need to construct a powerful narrative to defeat Banerjee. “She is bribing the voters,” won’t get any desired result.

Banerjee has a natural ability to connect with her constituencies which her opponents lack at the moment. Till that magic wand is found, they can eye the second-best position.