- Thursday, April 24, 2025

Annapurna Turkhud, a Marathi woman, developed an affectionate relationship with the Bengali poet and Nobel Prize winner when she was 20 and he was 17

By: Amit Roy

EDINBURGH has many links with India, but the latest, most significant discovery is the exact location of the grave of Annapurna Turkhud, a Marathi woman who developed an affectionate relationship with the Bengali poet and Nobel Prize winner Rabindranath Tagore, when she was 20 and he was 17.

Some scholars believe that Annapurna’s father, Atmaram Pandurang Turkhadekar, who headed a prominent family in Bombay [now Mumbai], proposed a marriage between the young couple, but this was turned down by Tagore’s patrician father, Debendranath Tagore.

The actress Priyanka Chopra Jonas wants to turn their story into a fullfledged Bollywood romance, which is possibly why she has not been given clearance to make the movie by the zealous guardians of the Tagore flame at Vishva Bharati University in Santiniketan in West Bengal.

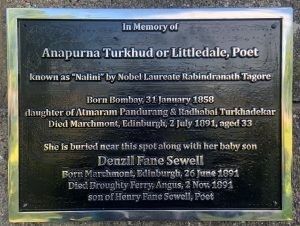

What is new is that the location of the unmarked grave in Morningside Cemetery in Edinburgh, where Annapurna (Anglicised to Anapurna or Ana) was laid to rest after she died shortly after childbirth on July 2, 1891, has been established.

What is also poignant that her infant son, Denzil Fane Sewell, who was born on June 26, 1891 and died on November 2, 1891, is buried with his mother. The baby was the result of an affair between Annapurna and a poet, Henry Fane Sewell.

Annapurna left her husband and their three children behind in Bombay and set sail for the UK with her lover, when she discovered she was pregnant. It is assumed she headed for Edinburgh because her brother, Dyneshwar, was studying medicine in the city. He was present when his sister passed away, aged 33.

On July 2, 2023, a plaque was put up on a wall adjacent to the grave on the anniversary of Annapurna’s death.

“There’s so much story behind it,” commented Hauke Wiebe, a Scottish tour guide and honorary fellow of the University of Edinburgh’s India Institute.

The plaque was unveiled by Prof Bashabi Fraser, who has been the director of Scottish Centre of Tagore Studies at Edinburgh Napier University and is the author of a number of books on Tagore.

The young Rabindranath was in 1878 sent from Calcutta to live with Annapurna’s family in Bombay, so that he could learn English and the ways of the British before being sent to London to study law. Annapurna herself had returned from a trip to England and was considered a suitable tutor for Rabindranath.

There was a family friendship between Rabindranath’s elder brother, Satyendranath, and Annapurna’s father, a progressive man who denounced the caste system and child marriage, supported widow remarriage, encouraged female education and sent all his three daughters to England to learn English manners. He served as sheriff of Bombay in 1879.

Bashabi and other scholars have pieced together what might have happened between Annapurna and Tagore, who gave his young tutor the poetic name, “Nalini”, meaning lotus, as she became his muse.

“Tagore writes that he half expected her to look down on him for what he called his own lack of scholarship, but she didn’t,” said Bashabi. “As for her nature, we can piece it from Tagore’s random jottings. We get impressions of a lively young woman hovering around a young Tagore, cheering him up in moments of homesickness, playing tug-of-war, flirting. She once told him whoever stole a young woman’s glove while she was asleep earned the right to kiss her and then she fell asleep promptly, gloves by her side.

“Tagore responded awkwardly to these affectionate overtures. But he writes about how he would try to impress this accomplished young woman by sharing his poetry. Their friendship teetered on the edge of something more. But Tagore was too shy to give in to her advances.”

She read a poem she had written for the occasion: “She sailed across the stage of his vision/ An embodiment of elegance, magically conversant/ In many tongues that mingled the essence/ Of the east and west in her expressive vitality./ He was overawed by her beauty and confidence,/ Her sophistication and gentle acceptance/ Of his tongue-tied presence, broken by his eloquent verse.”

Shortly after their encounter, Tagore sent sail for England, but had no interest in becoming a barrister and returned home without getting a degree.

As for Annapurna, in 1880 she married Harold Littledale, a Dublin-born professor of English literature and vice-principal of Baroda High School and College.

“Turkhud’s family was very progressive, very well regarded, very well known,” Bashabi said. “They had a very anglicised upbringing and education. For Littledale to marry into that family would have been quite appropriate for a British person.” They had three children, Ana Nelline (the second name is reminiscent of Nalini) (1880-1908); Olga (1884-1982); and Harold Aylmer Littledale (1885-1957) whose descendants have now been traced in America.

Bashabi said that Samaresh Tarkhad, from the fifth generation of Turkhud’s family in India, had been in touch with her. “They said she was totally lost to the family.” She added: “A lot of people didn’t believe me when I said I know she’s buried somewhere in Edinburgh.”

The search for Annapurna began in earnest when Roger Jeffery, professorial fellow in sociology and associate director of the India Institute at Edinburgh, first came across a reference to Annapurna in Bashabi’s 2019 biography of Tagore.

Jeffery, who has edited India in Edinburgh: 1750s to the Present and is co-author of the forthcoming Perspectives on India: Edinburgh’s Colonial and Contemporary Views, admitted he was initially sceptical about Bashabi’s story.

“I didn’t believe that,” said Jeffery, who has researched Scotland’s links with India for many years. “I would have come across her if this had been the case. As far as I could see, there was no evidence that she’d come to Britain after her first visit as a teenager.”

Jeffery, who has been working closely with Wiebe, said: “Then Hauke and Bashabi between them put together information that she did indeed come to Scotland and died here giving birth. And so I was wrong. Bashabi was right.”

Jeffery sought more information from a friend, Caroline Gerard, who said: “I’m a working genealogist. I can look up marriages, births, deaths, census returns, all that sort of thing – registration began in 1855 – to build up a family tree.”

Gerard found a death entry for Annapurna Turkhud, also named by her married name of Littledale, in 1891.

But “a death entry does not say where she’s buried”. Gerard, in turn, turned to someone who was an authority on cemeteries in Scotland – Peter Gentleman, structural inspector, bereavement services for Edinburgh City Council based at Mortonhall Crematorium.

He set to work after receiving an email from Gerard in January 2021: “Any sighting in your records of Ana(purna) or Anna(purna) TURKHUD or LITTLEDALE who died at 12 Warrender Park Crescent on 2 July 1891? The name SEWELL may get a mention, although it’s less likely. I’ve checked my gravestone listings in likely grounds, but nothing.”

Gentleman revealed how he found exactly where Annapurna was buried: “In the old days we would have to go through all of the burial books in turn for that date to find if she had been interred in one of our properties. I have spent some years copying the ledgers onto a computer database, so those searches are much easier to complete. We also had most of the books scanned so we can search those images instead of thumbing the actual physical copies.

“I opened the table for 1891 and scrolled down the names until I found Littledale. The address, date of death and alternative surname all matched so I knew I’d found the correct person.”

In Morningside cemetery, “I searched for a memorial on plot M316 from our safety inspection records and then found the exact location on the section map.”

He continued: “There are three interments in plot M 316. All three were full coffin burials. Annapurna Sewell was buried at 6 feet, then her son at 5 feet.”

There was another burial in the same grave from 1921 for a woman called Rebecca Annie Mowatt/ Tesdall. “The third interment is also given as 5 feet. This was common practice where a child had already been interred. Their coffin would be moved to the foot of the grave to allow for the full depth to be used.

“In the sales books Mr Henry FD Sewell purchased plot M 316 on 6 July 1891 for £14. His address is Co Thomas Cook & Son, Ludgate Circus London.

“There is an additional note from 29 July 1927 that £7 10/- was given in perpetuity. This must have been for upkeep of the ground and possibly for flower planting.

“For plots with a monument fixed to a foundation we normally assume that they are in the correct place and check them against the nearby memorials and the section maps to confirm the plot number. In this case the existing flat monument is not fixed and is slightly out of position. I measured from the large granite Bain headstone on the left and the Hutchison of Assam monument to the right, as these are on their original plots, to find the centre of plot M 316. These lairs (plots) are the traditional 3 feet in width and 9 feet in length with 2 feet being the border where the headstone is placed.”

For the unveiling of the plaque, Gentleman said he “marked the lair with green paint. The plaque is in line with the centre of the plot.”

Morningside Cemetery, which was 18 acres when it opened in 1878, is now 13 acres, with a fine avenue of lime trees in the middle. Among those buried there are Sir Edward Appleton, winner of the 1947 Nobel Prize for physics, and Allison Cunningham (“Cummy”) who was the nanny to Robert Louis Stevenson, author of Treasure Island, Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde and Kidnapped.

The unveiling of Annapurna’s grave was a moving occasion. Two Tagore songs were sung – Aamar Hiyar Majhe Lukiye Chhile (You were hidden in the inner recesses of my heart) by Payal Debroy and Dariye Aachho Tumi Aamar Ganer Opare (A stream flows between my song and you) by Gourav Choudhury – with Dhanajay Modak on tabla and Shubronil Bhadra on guitar.

Prof Alan Riach, a Scottish poet and academic, read Ye Banks an’ Braes o’ Bonnie Doon by Robert Burns and mentioned Tagore’s adaptation of the poem, and his own translation of the song, Shuno Nalini, Kholo Go Aankhi (Listen Nalini, open your eyes).

Two girls, Kirstin and Leyla, from the James Gillespie’s High School in Edinburgh, played the pipes.

Bijay Selvaraj, the Indian consul general in Edinburgh, commented that despite her tragically short life, Annapurna “was a pioneer in her day as a young woman travelling to the UK for an education”.

He urged the scholars “who have collaborated in this work to continue to tell the story of these connections between India and Scotland as this would benefit future generations to know about the close links that bind us”.

Jeffery said: “We’re here to remember Annapurna Turkhud, a woman who meant a great deal to Rabindranath Tagore at a certain period in his life. We’re here to bring Ana’s life to the attention of the people of Edinburgh because she came and died here, in Marchmont, tragically early, 132 years ago. I’m here because, for the past seven or eight years, I’ve been involved in a project to make visible in Edinburgh its India links. I used to call the project, at least in my own mind, ‘Edinburgh, an Indian City?’

“We cannot fully understand where Edinburgh is today without seeing how the Indian subcontinent contributes to this shared history. For two centuries, between the 1750s and the 1950s, India was a prominent feature of the lives of Edinburgh’s population.”

Jeffery later speculated on the breakdown in Annapurna’s marriage: “There’s no real reason why Victorian middleclass women’s lives should be any more straightforward than anybody else’s lives. She had an affair – her son was a result of the affair. And I think when she discovered she was pregnant, she rapidly left the country hoping to avoid this becoming public.

“My best guess, which is entirely a guess, is that Harold Littledale was a rather boring man. I think he was a bird watcher. My best guess is that the marriage became rather empty. And that Ana met this man who was a poet and was probably more exciting, more interesting than Harold Littledale. They fell in love and it ended up with her becoming pregnant, at which point she tried to deal with the situation by escaping to Edinburgh where her brother was a doctor in training.”

Annapurna’s husband later left India, returned to England, remarried, had three sons and daughter with his second wife and died in Bournemouth in 1930, aged 77.

Jeffery has been in touch with the descendants of Annapurna’s son, Harold Aylmer Littledale, who emigrated to America, became a newspaperman and won the 1918 Pulitzer Prize for reporting. He had a son called Harold Aylmer Littledale Jnr (1927-2015), who, in turn, had a son called Krishna Stephan Littledale (1957-2018).

The latter had two children: with his first wife, a son, William Ian Littledale (born 1987), and a daughter, Alexa Mary Fraser Littledale Curtiss (born 1994) with his second wife, Cynthia (her current husband adopted her, hence Curtiss has been added to her surname).

“Thus, my step-son and daughter are direct descendants of Ana Turkhud,” Cynthia has written to Jeffery, attaching a picture of the gold necklace Annapurna had once owned.

Edward Duvall, convener of the Friends of Morningside Cemetery, said that finding “a famous international figure buried in the cemetery” has been an important development for his group.

“We are a small group – fewer than 20 members – who spend our spare time carrying out gardening tasks in the cemetery. Anything that raises the profile of the cemetery, attracts visitors to this tranquil spot and helps forge international links gives us pleasure”.