“WHO was Churchill?” This was the question debated at the inaugural Chartwell Literary Festival last week at Sir Winston Churchill’s home in Kent.

It was held to mark the 70th anniversary of the Nobel Prize for Literature that Britain’s wartime leader was awarded in 1953. Introducing three historians on the panel – Allen Packwood, Professor Gaynor Johnson and Dr Victoria Taylor – the general manager of Chartwell, Chelsea Pettitt, said that Churchill “is viewed by some as the saviour of his nation, and by others as a racist imperialist. But who was he really? And how does he become such a controversial figure?”

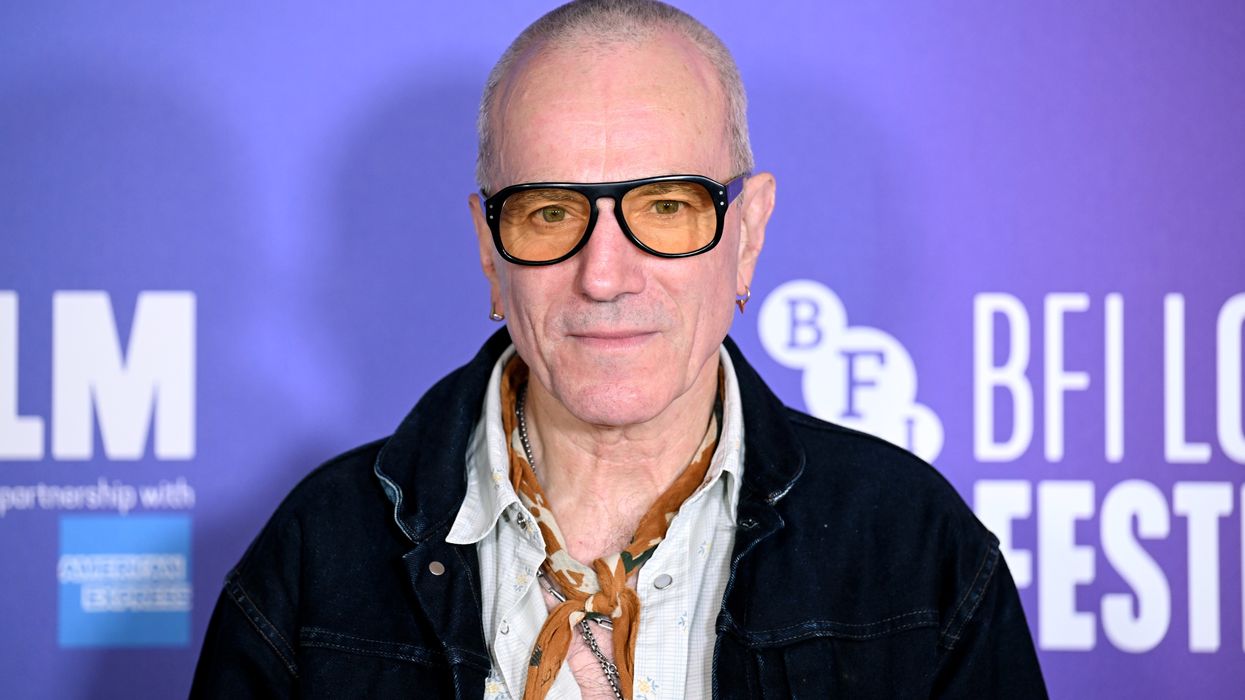

Packwood, the director of the Churchill Archives Centre at Churchill College, Cambridge, has recently edited The Cambridge Companion to Winston Churchill, which deals in part with the most controversial aspects of Churchill’s career – his opposition to Indian independence, his determination not to witness a dilution of the British empire and his hostility to Mahatma Gandhi.

The well-attended opening session in the Mulberry Room at Chartwell was attended by some of Churchill’s descendants.

Packwood, who is also a Fellow at Churchill College, said: “A lot of Churchill’s views on India are really formed very early on in his life and career when he goes out as a young soldier between 1895 and 1900. He’s very much a part of military there. That certainly colours his view on India.

“He tends to draw a distinction, which comes from serving in those military circles, between his admiration for Indian Muslim and Sikh troops, who he’s serving alongside on the North-West Frontier, and the wider Hindu population who he doesn’t regard anywhere near as favourably. His views on Hinduism, in particular, are formed quite early on.

“Later on, his campaign against Indian independence has to be seen in the context of British imperial decline, and what the country has been through in the First World War. Churchill wants Britain to remain a world power. And he sees having the empire as vital to that. He sees maintaining India as the centrepiece of that empire. So for him, regular Indian independence is moving away from that.

“The world that he grew up, that Victorian aristocracy is disappearing. The First World War has led to the collapse of empires. He’s seeing threats on all sides. And it’s for that reason that he particularly digs in on India. And that leads him to particularly oppose Gandhi.

“Churchill is someone who really has to have a cause. That’s how he conducts his politics. He likes high-profile public campaigns. The campaign against greater Indian independence is his main campaign at the beginning of the 1930s. Gandhi then becomes the enemy for that campaign in the same way that Hitler becomes the enemy over the need for British rearmament. Churchill needs these characters to vent against. A lot of you will have heard the quotes that he makes about Gandhi. Unfortunately for him, various of his colleagues in the cabinet are all keeping diaries and recording every remark that he makes.”

Packwood began by saying: “The title of this session is, ‘Who was Winston Churchill?’ And this might have struck some of you as a little bit strange. Surely, it’s obvious who Churchill was. He’s on the British fivepound note. He’s a man who’s practically omnipresent. He’s commemorated here at Chartwell, at his birthplace in Blenheim Palace, in the Churchill war rooms in central London, and at the Churchill College Archive Centre in Cambridge where I’m based.

“It’s rare that a week goes by without him appearing in newspapers or on television. He’s one of the most quoted, and it has to be said, misquoted figures of the modern age. He’s the subject of documentary series and films, most recently, Darkest Hour with Gary Oldman, and the focus of literally hundreds, if not thousands of books.

“His personal archive, which I’m lucky enough to look after in Cambridge, encompasses some 2,500 boxes. His official biography, started by his son Randolph and finished by the late Sir Martin Gilbert, runs to eight volumes, accompanied by a further 23 companion volumes, surely the largest official biography ever written. His collected speeches published by Robert Rhodes James run to another eight volumes and almost 9,000 pages of his spoken words. Everything connected with Churchill, it seems, is done on a monumental scale.

“His published speeches and his A History of the English-Speaking Peoples were vehicles that conveyed his world view. His output was simply phenomenal – some 14 published works in some 70 volumes over a 60-year span between 1898 and 1958, culminating in the Nobel Prize.

“After the Second World War, he told the House of Commons that it would be better for all parties to leave the past to history, ‘especially as I propose to write that history myself’, and write it he most certainly did. It led to an inevitable backlash because the higher Churchill raised his own profile, the more likely others were to react against it, either because they didn’t agree with his interpretation of events, or because to disagree with him guaranteed publicity and sales.

“In the book that we’re talking about, The Cambridge Companion to Winston Churchill, we have a chapter on Churchill’s contested history, tracing the origins of this process back into Churchill’s own lifetime, because the truth is that he has always been a controversial figure.

“So why do we need another book on Winston Churchill? Well, firstly, because it is deliberately short and accessible. It is not intended as another Churchill biography. It is not a hagiography, neither is it a hatchet job. It is intended as a gateway, as an introduction to a complex subject, which I hope summarises and synthesises the current state of academic opinion and research in a way that is accessible to a general audience.”

Packwood, who wrote the chapter on Churchill as a war leader, added: “The main point that we were trying to make in this book is that to understand Churchill, we need to understand him in a broad context. We need to see him in the round, not just in his own words, not in isolation, but as part of larger systems and structures. We need to understand how his views developed and evolved and how all aspects of the man interrelate. Because then and only then can the apparent contradictions in his history and legacy be resolved.”

While Taylor spoke of the controversial British bombing of Dresden in February 1945, which many regarded as unnecessary in military terms, Johnson advanced the defence that Churchill was a man of his times.

She said: “The opinions that Churchill expressed on issues which today we would see as very politically sensitive and controversial, like colonialism, were reflected by his generation as a whole. I don’t think they were necessarily particularly unusual. They were considered to be part of the way in which people of his background had been educated and had been taught to think.

“But the other thing I would say is that, as historians, we should judge historical figures by the context in which they operated rather than our own. Things that we think of as being offensive and controversial, things that we perhaps find difficult to talk about, may not be issues that were thought of in quite the same way in the past. We are on slightly dangerous – actually very dangerous – ground if we try to do otherwise.”

From the British Asian point of view, perhaps next year’s Chartwell Literary Festival will make less of an effort to “understand” Churchill.