- Saturday, April 05, 2025

By: Pooja Shrivastava

A REFUGEE, who arrived in Britain after Ugandan dictator Idi Amin expelled Asians from that country, has revealed how the UK gave him and his family a new life.

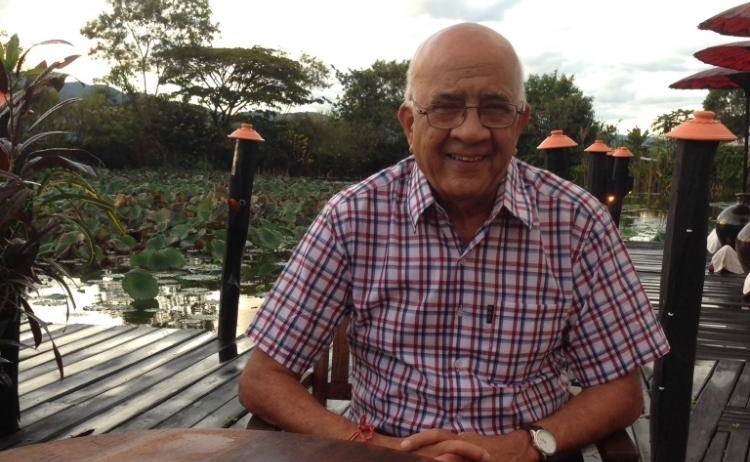

Mukund Nathwani, came to England in 1972 from Uganda at the age of 23.

“We were emotionally very disturbed people when we came here because we had to leave Uganda and save our lives. Luckily, the people in this country were very kind and the British government helped us find jobs and eventually we settled down,” the 72-year-old, who now lives in Birmingham, told Eastern Eye.

Nathwani was among the seven refugees, each representing one of the past seven decades, who came together recently to recreate the iconic photograph of the original signing of the 1951 UN Refugee Convention to mark its seventieth anniversary on Wednesday (28).

The convention formalised the rights of refugees under international law in England implying it was a legal duty to protect those fleeing persecution and serious harm in other countries.

With four brothers and three sisters and additional extended family members, Nathwani told how he had almost no financial support or capital when he moved to the UK. His grandparents had left India for Uganda, where he was born and brought up until the expulsion.

Upon arrival in the UK, Nathwani recalled being sent to a refugee camp where he received “a friendly welcome and respect for his vegetarian diet”.

“This country, that is the only capital we had, we had nothing else left. So we had to work really hard for the first 10 years to have our capital,” Nathwani told Eastern Eye, adding that he ran a series of successful shops and wholesale businesses until he retired.

“We don’t need government handouts. We are hardworking people. All we needed was an opportunity and a safe place for our family and we got that in the UK,” he said.

Nathwani explained how the UK supported people like him.

“When we were asked to get out of Uganda, a lot of people had Indian passports, but the Indian government did not give them as much assistance as we got in this country,” he claimed.

In the UK, the Nationality and Borders Bill is currently going through Parliament and was debated for the first time last week. If passed, it would mean that thousands of vulnerable people who would currently be accepted as refugees will no longer be given safety in the UK due to the method of their arrival. Some could be criminalised and put in prison for up to four years.

Nathwani said he saw no reason for changes to the way the UK processes applications by refugees and asylum seekers.

“The whole ethos, or thinking about refugees, changed after the UK signed the UN convention. Thanks to this, the UK was aware of its duty as a protector of asylum seekers,” he said.

“They were trying to help us as much as they could. I suppose this convention has worked so well for so many refugees like us.”

The campaign coalition, Together With Refugees, is calling for a fair and humane approach to the UK’s refugee system that allows people to have a fair and efficient hearing for their claim for protection; ensures people can live in dignity in communities while they wait to find out if they will be granted protection; enables refugees to rebuild their lives and make valuable contributions to their communities.

However, Nathwani acknowledged some people tend to take “undue advantage” of England’s stance on refugees.

“What’s happening is people who are not true refugees, they too are trying to come to this country, due to which, unfortunately, the genuine ones who really need asylum sometimes don’t get an opportunity because of some other people taking advantage. So this is where the filtering system should come or something should be done,” Nathwani said. “At the same time, refugees should not be forgotten,” he said.

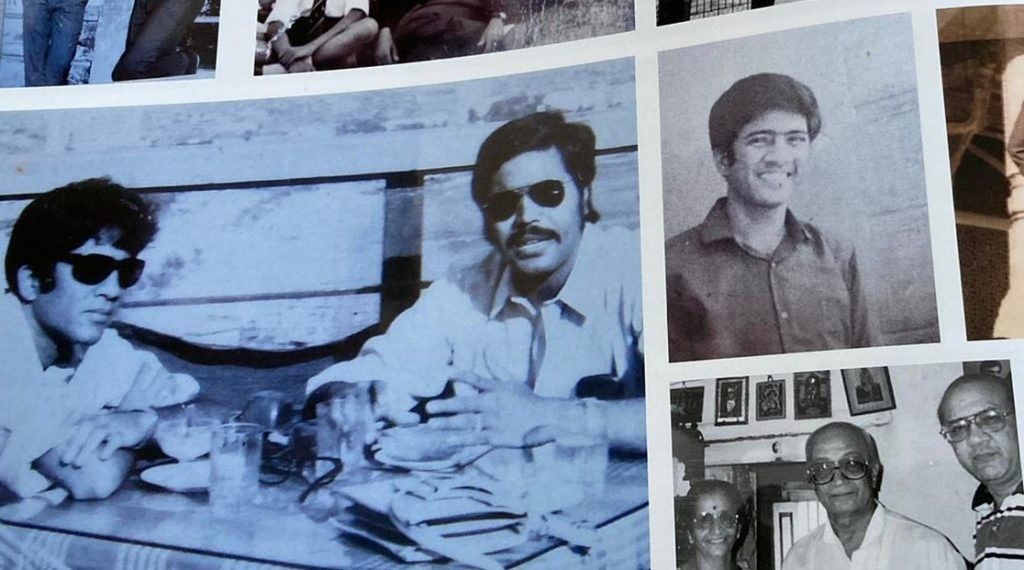

Identifying himself as a “proud British Indian”, Nathwani said he still feels connected to India. He often visits the country and spends time with his family in Gujarat. He has penned his memories in a book that has about 2,000 pictures, the oldest ones showing his grandfather’s initial days in Uganda from the early 20th century.

“Given an opportunity we can be successful, as we are very hardworking,” Nathwani said.