- Thursday, April 03, 2025

While political parties compete for power, factors such as military’s active role in politics, economic hardships and terrorist activities will see the new government up against a herculean task.

By: Adya Malik

AHEAD of Pakistan’s big electoral morning of February 8, the country’s winter mornings resonate with the anticipation of pivotal shifts towards peace, stability, economic recovery, advancements in healthcare, and the restoration of social equity within the nation.

The election to the 16th National Assembly is poised to unfold with established figures dominating the political landscape.

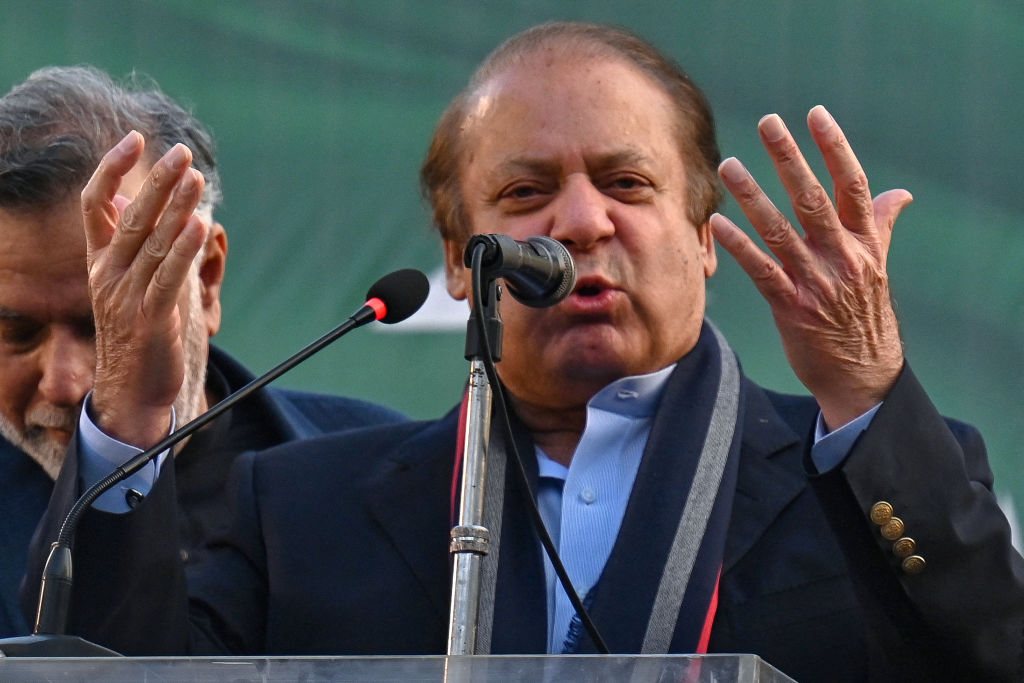

Among them, Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N), led by the three-time prime minister Nawaz Sharif, stands prominent as he returns from exile in the UK following his discord with influential figures in the country.

The Pakistan People’s Party (PPP), under the leadership of former foreign minister Bilawal Bhutto Zardari, and independent candidates from Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf, previously led by former prime minister Imran Khan, also vie for electoral success amidst the backdrop of the cricketer-turned-politician’s current legal challenges. Additionally, various regional parties contribute to the electoral tableau across different parts of the nation.

Read: Party with Mumbai terror-attack mastermind links contests Pakistan elections

The unfolding political narrative within Pakistan echoes familiar themes, as the stage appears to be set for Sharif’s resurgence, facilitated by the country’s influential figures, notably the military. This reflects a recurring pattern where the military’s involvement has historically influenced political dynamics.

Read: Ahead of Pakistan polls, PPP’s Bilawal Bhutto makes Kashmir promise

In 2018, the military’s purported intervention in politics led to Khan assuming power amid corruption allegations against Sharif. Now, with the latter’s return to power and Khan facing legal proceedings, this transition symbolises a strategic manoeuvre by the military, effectively substituting one political figure by another.

Pakistan’s democratic journey has been marked by challenges, with the military exerting significant influence behind the scenes. Over recent decades, the country has witnessed a lack of sustained democratic progress, with power dynamics often favouring the military over civilian governance. Notably, public sentiment consistently favours the military as the most esteemed institution, eclipsing trust in politicians, courts, and electoral authorities.

Consequently, no prime minister has completed a full five-year term since the country’s Independence in 1947, underscoring the enduring struggle to establish stable democratic governance. According to assessments by global democracy watchdog Freedom House, Pakistan’s electoral process is categorised as “partly free,” reflecting the enduring influence of the military within the political landscape.

As we transition our focus from the realm of political discourse to a broader perspective, the upcoming elections in Pakistan arrive amidst a backdrop of economic turbulence.

The nation grapples with a depreciating currency, soaring inflation rates, diminishing foreign reserves, outstanding debts amounting to $125 billion owed to external creditors and the daunting aftermath of natural calamities.

In conjunction, the incidence of terrorism experienced a marked escalation in 2023, resulting in over 1500 fatalities. Moreover, strained relations with neighbouring Afghanistan culminated in the deportation of approximately two million Afghan immigrants in the same year.

Additionally, Pakistan found itself embroiled in a significant confrontation with Iran following alleged airstrikes targeting separatist factions within its borders, prompting retaliatory measures from Islamabad—marking a rare instance of military engagement with Iran in nearly four decades.

Echoing these multifaceted challenges, Pakistani columnist Huma Yusuf in a column in Dawn titled ‘Revolution Now’ wrote — “The number of issues around which Pakistanis should be coalescing is staggering: food security, safety, dignity of work, free speech, minority rights, welfare protections, healthcare provisions, climate resilience. Until we can craft a politics that champions the people rather than against their overlords, our future will be riot, not reform.”

As a result, the prospect of transformative governance remains elusive and it can be seen through the palpable sense of disillusionment among citizens. This sentiment is evident in the persistently low voter turnouts witnessed over successive electoral cycles. Notably, the voter participation rate in 2018 stood at 51 per cent, marking a 10 per cent decline from figures recorded in 1970, with women’s turnout lagging behind men’s by 9.1 percentage points.

Moreover, across six of the past eleven general elections, the average voter turnout has hovered around 45 per cent, indicative of a significant proportion of eligible voters abstaining from exercising their electoral franchise. This phenomenon can be attributed to an array of factors encompassing scepticism toward the electoral process and institutional frameworks, deficiencies in education and political awareness, gender disparities, infrastructural shortcomings, and security apprehensions.

Amidst this, questions about the implications of the electoral outcome on India-Pakistan relations frequently arise. Notwithstanding, bilateral relations between the two nations have stagnated in recent years, with India adopting a largely non-responsive stance. While fleeting references to the prospect of normalisation of relations with India have been made, historical precedent underscores a cautious approach to such overtures.

Now as we anticipate the elections, we must note that nevertheless, human resilience and the enduring capacity for hope prevail, as the polling exercise rekindles aspirations for a more prosperous future for Pakistan. A future characterised by meaningful reforms, sustained peace, enhanced security, and robust socio-economic development remains the collective aspiration—a beacon amid prevailing challenges and uncertainties.

Adya Malik is a graduate in political science and International Relations and involved with the Chennai Centre for China Studies, India. She is proficient in Mandarin and passionate about fostering positive change through communication and advocacy.