- Friday, April 04, 2025

By: Shelbin MS

EVER wondered what the priest is actually saying when he leads prayers in Sanskrit at Hindu religious ceremonies?

Most people tend to repeat the words after the priest without understanding what they mean but now help is at hand. Prof Diwakar Nath Acharya, who is the Spalding Professor of Eastern Religions and Ethics at Oxford University, is about to set up the Sanskrit Text Society for the benefit of the lay person.

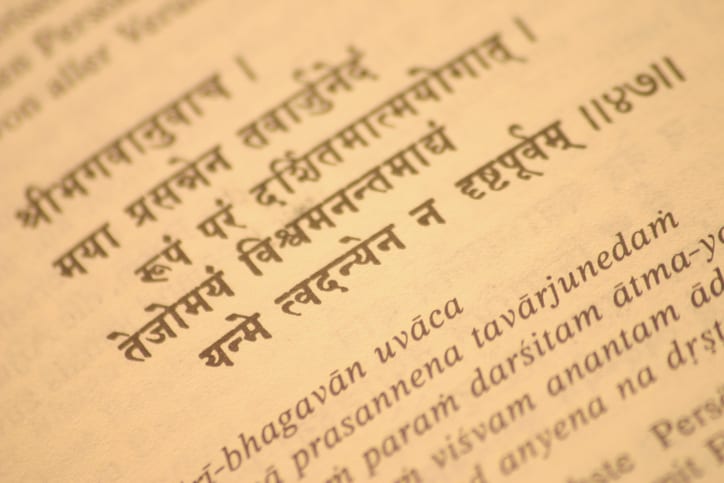

He points out that the two great Indian epics, the Mahabharata and the Ramayana, were written in Sanskrit, as was the Bhagavad Gita, Krishna’s discourse with Arjuna in the field of battle, which is part of the Mahabharata. The explanation for yoga is also in Sanskrit.

In fact, for an understanding of India, it is vital to go back to ancient Sanskrit texts, says Acharya, who is currently editing the Book of Wisdom.

“These are nice sayings – 800 verses on different topics but all collected from the Mahabharata,” he discloses.

Acharya, who was born in Nepal, came to Oxford from Kyoto University where he was associate professor of Indological Studies. He was previously research associate at Hamburg University and an assistant professor at Nepal Sanskrit University.

Part of Acharya’s job is scholarly – publication and translation of unpublished Sanskrit texts which are to be found throughout south Asia. But an important part of his mission is also to make Sanskrit accessible to lay people. Hence, he is setting up the Sanskrit Text Society.

Acharya, 50, took over the Spalding chair four years ago. It was established in 1936 and held until 1952 by Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, who went on to become president of India in 1962.

The chair – one of the most prestigious in the academic world – was established by philanthropist Henry Norman Spalding and his wife, Nellie, whose family had made its fortune in shipping and guano trading, “to promote intercultural understanding by encouraging the study of comparative religion”. The chair was recently re-endowed by their granddaughter, Dr Anne Spalding.

“These days I am dreaming of establishing the ‘Sanskrit Text Society’ or ‘Society for the Study of Cultural Heritage of India’ as a charity to publish Sanskrit texts and their translations, and also serve as a platform for exchange between Oxford-led specialists of Indian Studies and the Hindu community in the UK,” Acharya says.

His plans include holding monthly evening gatherings in Oxford or in London to discuss the cultural and intellectual heritage of the Indian way of life and study classical Sanskrit texts; and organising webinars and classes to study Hindu, Buddhist and Jaina philosophies.

“We also aim to launch a composite book series for the publication of classical Indic texts, their anthologies and adaptations,” he adds. “We are eager to identify and publish rare, hitherto unpublished ancient texts preserved in fragile manuscripts. An open-access online journal can also be launched.”

Membership of the Sanskrit Text Society will be open to anyone who is interested in learning about India.

Acharya says Sanskrit has contemporary relevance. “What makes us Asian people different is our way of thinking and our world views guided by distinct ideas, for example, the theory of karma and rebirth. Therefore, to understand ourselves, we need ancient texts, and for the right understanding of ancient texts, we need to read them carefully.

“For example, what is the message of the Bhagavad Gita? A religious preacher would say devotion to the godhead, but I would say, devotion is a means and the goal is self-cultivation and equanimous skilfulness in action. Yoga is for skilful, mindful and equanimous action.”

He tells British Asians: “We would like to remind the community that Hinduism does not end in temple worship and stories of the Puranas, nor in the other-worldly approach of sannyasa, or miracle and charisma of a guru, or astrological obsession. The aims of the Hindu way of life should be self-cultivation with this-worldly approach of the original Vedic texts. By the way, the Vedic world view was not this much world-denying. They wanted to overcome their troubles, but they did not one-sidedly see the world as suffering. Instead, ancient people wanted to come back to this world again even as plants and trees near their descendants.

“Indian religions originally worshipped deities as role models and imitated them, but nowadays the real message is lost in myths, metaphors, and stories. They are needed for every nation and community in every age, but we have to go beyond metaphors and read the message for the sake of cultivation of divinity in human life.”

According to Acharya, “we need to reinvent ancient teachings and ancient wisdom for modern times. Ancient texts are like vast oceans, but we can come together to gather tiny gems from the scriptures, the Vedas, the Upanishads, the epics, and Dharmashastras, the philosophical treatises, and many other texts.”

Climate change is not a new concept because the ancient texts “remind us basic but important truths: care for nature and environment, earth and heaven, balance in life”.

He set out his vision for the Sanskrit Text Society: “Let us come occasionally together in a pleasant and relaxed environment and discuss Asian culture and values.

“At times, we can simply read recite and sing ancient texts, Sanskrit, Prakrit and Pali poems, enjoy the aesthetic beauty of these languages. Some other times, we can have more serious and in-depth analysis of difficult texts and ideas. But we should come together to preserve, enjoy, analyse and reinvent the treasure of our heritage.”

In his inaugural lecture in October last year at the Exam Schools in Oxford, Acharya pledged: “I will do my best to create an abiding interest in the religions and the ethical systems of the east at Oxford, drawing on my knowledge, training, and experience of Indian religions, mainly Hinduism and to some extent Buddhism also.”

He referred to his famous predecessor: “As Radhakrishnan stated, ‘Religion is not so much a revelation to be attained by us in faith as an effort to unveil the deepest layers of man’s being and get into enduring contact with them.’”

Acharya also clarified: “I should make it clear that I use ‘India’ and ‘Indian’ in the sense of culture and civilisation beyond political and even geographical boundaries. Huge confusion has been caused by the failure to distinguish between contemporary political India and cultural India.

“As a Nepali myself, I am of course particularly sensitive to this point – the distinction between India the modern nation-state and India the cultural area must constantly be kept in mind.

“The classical Indian religion now recognised as Hinduism is, in fact, a conglomeration of many ancient and mediaeval traditions. Many of them have been transformed through the ages.

“In order to understand the process of development and transformation of these traditions and also their modern incarnations properly, it is necessary to study and analyse rare and otherwise unknown texts preserved in manuscript archives.

“This will help us to understand not only the features of traditional Indian societies, but also the complexities and peculiarities of modernism in India. This will prevent one from wrongly identifying the self and the other and also help to guard against erroneously reading back the concepts and realities of the present into past times.”