- Friday, April 18, 2025

Young, well-educated and an administrator with a decade’s experience, the Aam Aadmi Party leader has led his party to power in two Indian states, something that no other regional party done at this moment.

By: Shubham Ghosh

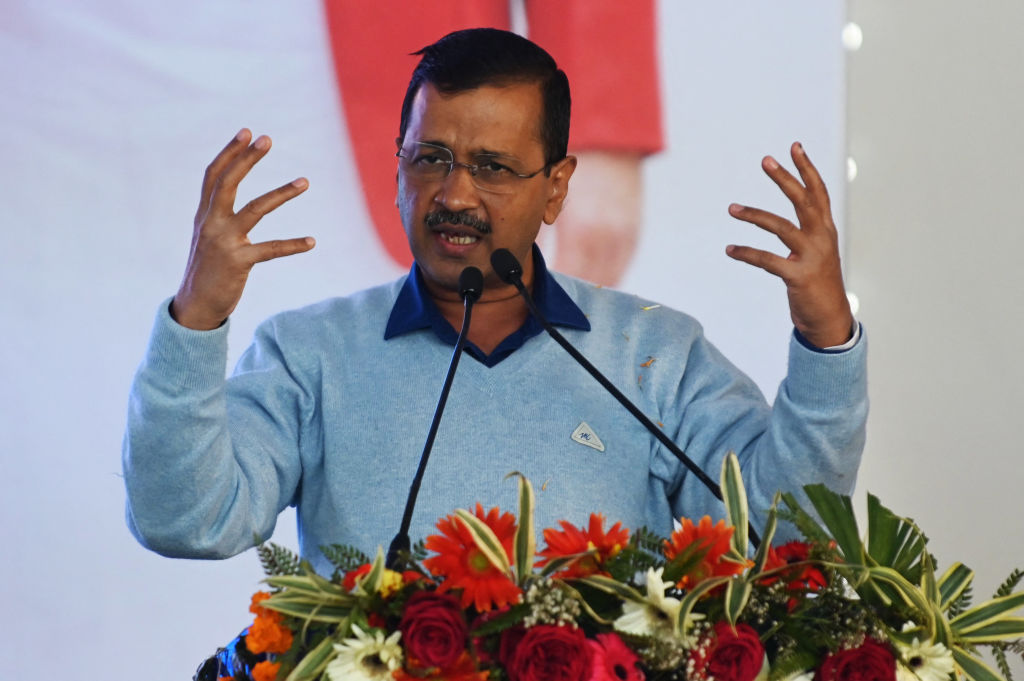

ARVIND KEJRIWAL is an enigma of Indian politics. In a country and at a time when politicians are often seen as a lot that repulse more than attract, the 55-year-old leader of the Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) was seen as someone who gave a new hope — against a decaying political system.

The rise of Kejriwal happened at a time when Indians were very angry with rampant corruption in the second government of former prime minister Manmohan Singh. As the United Progressive Alliance II government was left battered with endless charges of corruption, India saw a renewed politics of street protest, reminiscing the Gandhian days during the colonial era.

The India Against Corruption platform was formed, spearheaded by veteran Gandhian leader Anna Hazare, and among his many colleagues was Kejriwal. The movement demanding for an ombudsman against corruption had seen a massive response across the country. More than the success of the movement, what had impressed people is the birth of a new democratic politics, potentially looking lethal to defeat the behemoth of corrupt politics.

Read: Huge blow for India opposition as Delhi CM Arvind Kejriwal arrested in graft case

Kejriwal, a mechanical engineer by training, alumnus of the prestigious Indian Institute of Technology – Kharagpur in the eastern state of West Bengal, and a former Indian Revenue Service official, became widely followed as an activist — an award-winning one. His decision to join politics was not something that everybody in IAC, including Hazare, supported. But Kejriwal’s popularity reigned over everybody else and his Aam Aadmi Party (AAP) soon appeared. That was towards the end of 2013.

Read: Delhi CM Arvind Kejriwal’s arrest sparks protests across India

Kejriwal’s primary agenda remained corruption, as it was on this particular issue that the movement-turned-political party had started. The leader, who was seen in a muffler and cap in his earlier days, soon became a symbol of a crusade against corruption. The party symbol of broom suggested sweeping away the evil of corruption.

The AAP tasted electoral success in its very first election, when despite not getting a majority in the Delhi assembly elections, it formed a government in the state with the backing of the Indian National Congress, the party against which it had been working all this while. He defeated the incumbent chief minister of Delhi, Sheila Dikshit, to create a sensation. But drama soon followed as Kejriwal quit his post just after 49 days of coming to power after failing to pass a legislation on ombudsman against corruption in the Delhi assembly.

A presidential rule was proclaimed in Delhi following the collapse of the government. The newly formed party also decided to contest the general elections that followed in early 2014 and fielded candidates in as many as 432 seats. Kejriwal himself stood against prime minister Narendra Modi in Varanasi. He lost and the AAP could win only four seats.

While many criticised Kejriwal over his drastic resignation, there were also people who considered him a hero — one who never compromises with the moral fight against corruption even as the leader of a government.

Kejriwal later overcame these failures by overwhelmingly winning elections twice in Delhi (2015 and 2020) and also leading the party to come to power in the northern state of Punjab in 2022, something that even Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party has not been able to do till date. It has also done well in emerging as a top contender in Gujarat, the home state of Modi, challenging the ruling BJP at the expense of the Congress, the main opposition.

But just when the AAP was looking to put in place a major plan for the next general elections and also made seat-sharing agreements with the Congress in many states, except Punjab where it decided to contest alone, Kejriwal was arrested in a liquor policy scam. This is undoubtedly a major blow for the party which continues to give hope to a major section of the electorate who are against Modi’s BJP.

It is ironic that the Delhi chief minister and a number of top leaders of his party have found themselves in jail in connection to corruption, something that the AAP always vowed to fight. But this was perhaps not too surprising, because the AAP is perhaps the only party that can pose a challenge to Modi’s formidable BJP in the long run from now.

Kejriwal, convener of the AAP, looks to be the only opposition leader at the moment who can go on to create a counter narrative in Indian politics, something more senior campaigners such as Rahul Gandhi of the Congress, Mamata Banerjee of the Trinamool Congress or Sharad Pawar of the Nationalist Congress Party are unlikely to achieve.

For one, Kejriwal is young, well-educated (a trait still considered rare among Indian politicians), runs a government and leads a party that aspires to be a national force. Unlike many older regional parties, the AAP has already been in power in more than one state in the era of Modi wave and that’s no mean achievement.

In Delhi, where the top brass of the BJP live, Kejriwal’s AAP has denied the Hindu nationalist party a taste of power in three successive elections. While Modi’s party has hammered it in the general elections in Delhi, it has succeeded little in curbing the AAP government’s popularity earned through welfare schemes in the small state.

Also like Modi, Kejriwal is one of those few Indian politicians today who has a decent following among the youngsters.

It is true that despite not endorsing factors such as religion or caste, Kejriwal has adopted a policy of strategic silence in the past in times of Hindu-Muslim violence in Delhi. Many accused him of showing more solidarity with the majority community and not the minority community and thought the AAP’s promise of opposing ‘divisive politics’ to be empty.

But one would suspect that such a strategy was needed by the party which is still much smaller when it comes to fighting a powerful opponent such as the Hindu nationalist BJP in a Hindu-majority nation.

The AAP’s disadvantage lies in the fact that only contesting on the plank of corruption is unlikely to succeed much in today’s Indian politics. The problem with such a position is that when Kejriwal shares a stage with someone like Lalu Prasad Yadav, a politician convicted of corruption, while displaying the opposition unity against Modi, his image takes a serious beating and gives the BJP ammunition to target him and his party.

That leaves the AAP with populist policies to build its electoral base. But by just being an urban-centric and populist party, can Kejriwal’s AAP hope to last the distance and dethrone Modi?

Kejriwal, one would believe, is still a leader of the future — perhaps for the post-Modi era. With no other opposition leader in the country succeeding in building a credible alternative and the BJP facing the task of finding a successor to Modi, 74, in a few years from now, the AAP leader could have an opportunity coming his way. He has the election in Delhi lined up next year. If the previous years’ results can be replicated there in 2025, Kejriwal, despite his current trouble, could rise as the next big opposition face in Indian politics to challenge the post-Modi leadership in the BJP in 2029.

As of now, he has to find a way out of the mess he has found himself in.